Refugee is much more than just a ‘crisis’, as it’s generally relegated to in popular narratives in media or intellectual discourses. There’s a United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and there are the United Nation’s 1951 Refugee Convention and 1967 Refugee Protocol. It’s not that the world is not all ears to the wails of the refugees, but perhaps only a refugee knows the real pain of being a refugee. No convention or protocol can ever do justice to a refugee. Few lines from a popular poem by the Bengali poet Krishna Chandra Majumdar might be apt: Always pleasure loving, someone seldom feels the agony of distress. How will he know how painful the poison could be, if he has never been bitten by a scorpion?

The Bengali word for refugee is udbastu, which loosely translates to homeless in English. The word “bastu” or “vastu” in Sanskrit derives from the root “vas” – akin to the English “was” –, which signifies not only a dwelling, but also existence. So “ud-vastu” would mean someone without existence, not just homeless, and that’s perhaps the word which conveys the real meaning of refugee, only to some extent though. There might not be ever a complete remedy for a refugee’s real agony and trauma, but still, if she got someone who could empathize with her, listen to her stories, make her feel that she’s no longer alone in the new world, that would surely act as a soothing balm, calm her down a bit. The biggest enemy of a refugee is not the perpetrators who has raped her or uprooted her from her home. Her biggest enemy is perhaps the feeling of loneliness, the loss of her self-confidence and trust on others. The only way anyone can help a refugee is by gaining her trust, reviving her confidence in herself. And hearing her stories, feeling her pains is perhaps the best way to let her know that that someone is there for her, that she’s not alone any more.

The voluminous narratives about the Jews in the popular culture, art, literature and movies over the past hundred years perhaps created the most effective support system for them, while they struggled to cope up with their bereavements, uncertainties and fear for the unknown in newer lands. The very fact that the whole world has wept for them gave them a sort of psychological security, even though they might not have got any real support from anyone in their lonely struggles to create their worlds anew, from scratch, bit by bit. The most unfortunate thing about the seven to eight million Hindus of East Bengal, who became refugees after the partition of India in 1947, and the many thousand more who wanted to flee East Pakistan and then Bangladesh later, there was no one even to empathize with them, because their very existence remains unacknowledged till this day. It is, as though, they never existed.

Whenever anyone talks about or refers to the partition of India, it’s always the Punjab side of the story – it’s seldom the Bengal side. There’s a total lacuna in the awareness, and also information, about the Bengal side of the narrative, except for the extensive oral traditions, which have survived even after a few generations among the East Bengali Hindus worldwide. I myself grew up with a staple dose of stories from the hallowed homeland of my family in East Bengal. Even though I never visited East Bengal, now Bangladesh, I still have a vivid idea of our home and village, over there, the rivers, the vast green fields, the floods, the flea markets, the village fares, the crops, the festivals, and of course the horrific conditions under which my father’s family had to suddenly flee their homes, leaving behind everything. The sad part is that, these stories were never heard outside Bengal. Not only that, there has been always a concerted effort at various levels to brush the Bengal side of the partition narrative under the carpet. This particular aspect needs to be talked about.

Let’s rewind a bit and see what exactly had happened in 1947, when India was trifurcated into three moth eaten parts – with India at the center and the disjoint West and East Pakistan at the two sides. The idea was to carve a Muslim majority Pakistan out of the undivided Indian subcontinent. The original Muslim League demand was for a Pakistan comprising the whole of the five Muslim majority provinces, the Punjab, Sind, Baluchistan, and North West Frontier Province (NWFP) to the west and Bengal to the east, and also, curiously enough, Assam, a Hindu majority province, adjoining Bengal in the northeast. But, given that Punjab and Bengal had considerable proportions of non-Muslims – mainly Sikhs and Hindus in the Punjab and Hindus in Bengal – and the serious concerns looming ahead about their wellbeing in the totalitarian Muslim regime, the Congress and the Hindu Mahasabha, in the interest of the non-Muslims in these two provinces, convinced the British government to partition the Punjab and Bengal and retain the non-Muslim majority portions in India.

Accordingly, the Punjab and Bengal provinces were partitioned. The western part of the Punjab, comprising the contiguous Muslim majority districts, became a part of Pakistan, retaining the eastern part in India. A similar formula was applied for Bengal. The Muslim majority East Bengal, designated presently as East Pakistan, was attached as an appendage to Pakistan, separated from the western part by more than 1000 miles of Indian landmass, which retained the Hindu majority West Bengal.

Figure 1: Partition of India - 1947

The extraordinary misfortune of the Hindus in Bengal started with the boundary itself, of the partitioned province. Some facts and figures here would make things clearer.

Oscar Spate, an eminent geographer and an unofficial advisor to the Muslim League, especially on the matter of the desired boundary of the Pakistan side of the Punjab, said in the paper The Partition of the Punjab and of Bengal, published in December 1947 in The Geographical Journal, "I favor the Muslim case in the Punjab … and in Bengal my leaning is towards the other side." [1] In the same paper he elaborated why he said so.

The proposed boundary in the Punjab left 3.5 to 4.5 million minorities on either side. Western Punjab had a population of 15.8 million, of whom 11.85 or close to 75% were Muslim, and the rest 25% predominantly Hindu and Sikh minorities. East Punjab had a population of 12.6 million, of whom 4.4 million or roughly 35% were Muslim minorities. Presently, both sides have only around 3% minorities. Almost the entire minority population changed sides soon, amidst the fast deteriorating atmosphere of insecurities and brutal violence of unthinkable magnitude inflicted upon the minorities on either side. Enough has been written about this violence and the Punjabi, Hindi and English literature have a significant volume of poignant narratives of the horrors of this chapter of the partition.

The boundary of the partitioned Bengal was unduly favorable to the Muslim side. For example, whole of Khulna district with 49.3% Muslim population was awarded to Pakistan, for reasons even Spate couldn’t figure out. West Bengal had a population of 21.2 million, of whom only 5.3 million or roughly 25% were Muslim minorities, whereas East Bengal had 39.1 million people, of whom a staggering 11.4 million or roughly 30% were predominantly Hindu minorities. Presently only 8% of East Bengal, now Bangladesh, is Hindu, whereas West Bengal is still 27% Muslim, compared to 25% at the time of partition.

Figure 2: Displaced People & Migrations after Partition

By 1948, as the great migration drew to a close, more than 15 million people had been uprooted, and between one and two million were dead. [2]

Anything between seven to eight million of the 11.4 million Hindus were forced to flee East Bengal or East Pakistan and seek refuge in West Bengal and other parts of India, over the years, in a staggered way, during which there was formidable resistance even from the newly formed India government in accepting them, or even acknowledging their status as displaced people, forget settling them respectfully. On the contrary, as pointed out by a Bangladeshi writer in an article published in the New York Times during the seventieth anniversary of the partition of India, “only 700,000 moved to East Bengal… Bengali Muslims suffered less violence than other groups. For many of them the move was voluntary, indeed opportunistic… [in the] hope of a better future, rather than the mere search for a safe haven.” [3] We will try to figure out the plausible reasons behind this later. For now, let’s put the numbers in perspective.

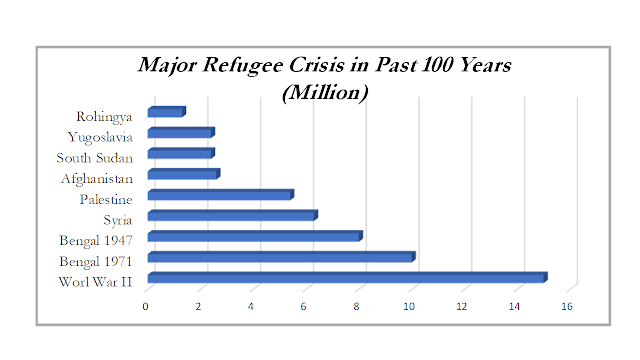

Figure 3: Bengal Partition and other major Refugee Crises in the World

The World War II created something between 11 to 20 million homeless people, displaced from their original homeland. [4] Indian partition created 15 million, [2] out of which only the Hindus from East Bengal (“Bengal 1947” in Figure 3) comprise a staggering seven to eight million. What’s interesting is though the fact that the latter gets almost no space in the entire narrative about Indian partition both in India and elsewhere, as if, they never went through anything called partition, whereas they might be the second largest displaced community in the world, only after the Jews. Again, let’s take some examples here, to understand what I mean.

There were a number of articles in the Indian and western media in August 2017, commemorating the seventieth anniversary of the partition of India. One in the Washington Post, 70 years later, survivors recall the horrors of India-Pakistan partition, [5] doesn’t mention anything about the Bengal partition, even as a passing comment. Another in The Guardian, ‘Everything changed’: readers’ stories of India’s partition, [6] and one in Daily Mail, The children of Partition remember the bloodshed and heartbreak 70-years after India-Pakistan split, [7] also have no reference to Bengal. Even India Today, in an article published in its August issue in 2017, True-life tales of families separated during Partition, [8] gives Bengal a total miss.

Not only in the media, the art and literature too give the Bengal partition a near total miss. A list of the 25 best books about Indian partition, compiled by Penguin in August 2017, [9] includes the likes of Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children, Ismat Chughtai’s Lifting the Veil – a collection of his Urdu writings, Nisid Hazari’s Midnight’s Furies: The Deadly Legacy of India’s Partition, Kamleshwar’s Hindi novel Kitne Pakistan (How many Pakistans?), Krishna Baldev Vaid’s autobiographical Hindi novel Guzra Hua Zamana, translated into English as The Broken Mirror, three translations of the Urdu works of Sadat Hasan Manto, Bhisham Sahni’s Hindi novel Tamas and Khuswant Singh’s Train to Pakistan, among others, most of which deal only with the Punjab side of the partition. The obscure The Train to India by Maloy Krishna Dhar is the only one in the list which deals with the Bengal side of the partition in a similar way.

Given the prolific Bengali literature and the epoch creating works by some of the finest writers of our times who have lived through the partition, it’s indeed very unusual why none of them wrote anything on the horrors of the partition. Sunil Gangopadhyay’s three volume magnum opus Shei Samay (Those Times), Pratham Alo (The First Light) and Purba Paschim (East & West), about the history and evolution of Bengal, the Bengalis and the Bengali culture and geopolitics over the past two centuries, spans through the period of the partition of Bengal in 1947 and the liberation of Bangladesh in 1971, but surreptitiously bypasses the horrors of the partition, thus depriving the Bengalis and the Bengali literature of the partition narrative so poignantly created by the likes of Krishna Baldev Vaid, Bhisham Sahni, Khushwant Singh, Amrita Pritam Singh and Sadat Hasan Manto in Hindi, Punjabi and Urdu.

In the review of Krishna Baldev Vaid’s Broken Mirror in India Today, [10] the reviewer points out, “Nearly every Punjabi writer, from Bhisham Sahani to Amrita Pritam, has at least one opus about the horrors of Partition. It is the Indian genre of civil war writing, a geopolitical literature which is no doubt the compulsive muse of any aspiring writer of that particular cultural experience.” It’s indeed a big exception that not a single contemporary Bengali writer found the Bengal partition an experience moving enough to be chronicled. The victims of the Bengal partition, predominantly the Hindus of East Bengal, are deprived here too.

The prolific Bengali filmmaker Ritwik Ghatak’s partition trilogy Meghe Dhaka Tara (The Cloud Capped Star, 1960), Subarnarekha (The Golden line, 1962) and Komol Gandhar (E-flat, 1961) are among the best works in Bengali touching upon the problems created by partition.

But here too, Ghatak bypasses the horrors, violence and genocide during the partition and rather deals with the agony and trauma of the refugees, their insecurities, nostalgia for the homeland they had to leave and their struggle to sustain their existence in the alien land they are trying to make their homes. So technically, his works are refugee narratives, not partition sagas. Even more correctly, as pointed out by Anustup Basu, faculty of English, Media & Cinema Studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign (UIUC), at a panel on Borderland Narratives of the Bengal Partition, organized by UIUC in April 2019, Ghatak’s trilogy, and many other movies in the 50s and 60s in both Hindi and Bengali were “filled with different kinds of loneliness.” In Basu’s words, they were “melodramas of loneliness. That of negotiating loneliness in a strange and alienating city.” [16]

In this context, Basu invokes an apt line from Rahi Masoom Reza’s memorable 1966 novel Adha Gaon (Half Village). In rough English translation, it goes like this: “In short, with independence, several kinds of loneliness had been born.” Basu also refers to Bhaskar Sarkar’s book on the Partition and Indian Cinema, Mourning the Nation, where the author says that “in the first few decades after independence, there was very little cinema made, either in Bombay or Bengal, that directly addressed the Partition”. Sarkar forwards a Freudian explanation for this – a culture needs some time to absorb, work through trauma before it can start talking about it.

Looks like, the Hindi cinema overcame the trauma and the loneliness of partition, but the Bengali didn’t. Or is it that, the intellectual and over sensitive Bengali film makers pretended to have never overcome the trauma, and just kept silent?

Now, let’s delve into why the Bengal partition has been totally neglected in all spheres – politics and arts. We need to again do a rewind.

The Government of India Act 1935 gave a good amount of autonomy to the 11 provinces of British India and paved way for the first Provincial Election in 1937. Congress got majority and formed governments in eight of the 11 provinces. The secular Unionist Party representing the interests of the feudal class of the Punjab and supported by the Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs, formed the government in the Punjab. Congress with 54 seats, was the single largest party in Bengal, but didn’t get a majority. AIML, All India Muslim League, led by Jinnah, later the first President of Pakistan, failed to create government in any province. But it got 85% of the total Muslim votes across all the provinces, vindicating its stand and claim that it was the only party representing the interests of the Muslims. This implied that the Congress was not the party of the Muslims, as claimed by Jinnah. This also implied that the Congress, in contrast, was the party of the Hindus – notably, apart from Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, there was no other prominent Muslim leader in Congress either. This was not acceptable to the Congress, which, under the idealistic Gandhi, couldn’t swallow the Hindu tag. [11]

Perhaps that was the beginning of designating anything associated only with the Hindus as ‘communal’. Now, to shed its ‘communal’ tag, the Congress went all out to woo the Muslims to its sides, and started a mass contact program. That was perhaps the beginning of the legacy of Muslim appeasement in India, just for gaining some political mileage, something that later acquired dangerous proportions with more dangerous consequences in Indian politics.

This did more damage than good, as the Muslims became suspicious of Congress’ intention and agenda. To top it up, Jinnah raked up enough fear among the Muslims against their fate in a majoritarian Hindu regime under Congress. So neither did the Muslims get attracted to the Congress, nor was the latter ready to be seen as a Hindu party. Such was the zeal to remain ‘secular’, that the Congress didn’t want to form a coalition government in Bengal even with Fazlul Faq’s Krishak Praja Party (Peasant’s Party), which had 36 seats, one less than the League. It was as though, entering into a coalition with a ‘Muslim’ Party would have branded Congress as a counter ‘Hindu’ party. In doing so, as Tathagata Roy points out in My People Uprooted: The Exodus of Hindus from East Pakistan and Bangladesh, [12] [13] the Congress lost a golden chance of keeping at bay the League hardliners like Suhrawardy or Nazimuddin, who later became Prime Ministers of Bengal and inflicted irreversible damages to the social and political structure of Bengal. We’ll come to that soon. Fazlul Haq, who didn’t have good relations with the League, felt betrayed by the Congress, and went ahead reluctantly to form the government in Bengal with the League, which remained in power till the last day of the undivided Bengal.

In the next provincial election, in 1946, the League formed governments in Bengal and Sind, and the Congress in the rest of India. In the Punjab the Congress entered into a coalition with the Unionist party and formed the government. League’s Suhrawardy became the Prime Minister of Bengal.

As a part of the process to handing over India to the Indians, the Cabinet Mission came to India early 1946, for setting up an Interim Government to form the Constituent Assembly, which would be creating the constitution of the free India. In its “16 May” statement, the Mission proposed a three tier structure, where the “Provinces” would be at the bottom, Hindu and Muslim “Groups” of provinces would be in the middle and the “Indian Union” at the top. It was proposed that the five Muslim majority provinces – the Punjab, Bengal, Sind, Baluchistan, NWFP – and, curiously again, the Hindu majority Assam, could merge into two Muslim-majority “Groups” in the Union.

Jinnah accepted 16 May. Congress didn't – they waited for the Interim Government to be formed and then play the cards.

In the subsequent “16 June” statement, the Mission announced the Interim Government, with no Muslim member from the Congress side. Understandably, Gandhi was vehemently against an all Hindu Congress team. The Clause 8 of 16 June said that if the statement was not acceptable to any party, then the Viceroy would unilaterally proceed with the formation of an Interim Government, which would be as representative as possible of only those willing to accept 16 May.

Jinnah thought Congress would reject 16 June and expected to form a new government without the Congress. But at the last moment, defying Gandhi, the Congress accepted 16 May, evoking protests from Jinnah, who insisted the Viceroy shouldn’t accept Congress’ late acceptance of 16 May, to which the Viceroy didn’t relent.

Jinnah declared Direct Action Day on 16th August 1946 – “Direct Action” to achieve Pakistan. Rajmohan Gandhi, in his magnum opus Mohandas, [11] quoted Jinnah as saying, “Today we bid goodbye to constitutional methods.” What ensued was mayhem in the streets of Calcutta, killing thousands of Hindus. On 20th August the British owned The Statesman reported, “The origin of the appalling carnage – we believe the worst communal riot in India’s history – was a political demonstration by the Muslim League.” The Great Calcutta Killing, as the daily reported it as, unleashed the chain reaction of communal riots in India, something which would attain more sinister forms in the next hundred years. The Suhrawardy government in Bengal did literally nothing to stop the killings in Calcutta. That was the beginning of the Hindu genocide in Bengal, something which would be very soon brushed under the carpet. The Great Calcutta Killing is the mother of all communal riots in India, setting off an unending fission chain reaction of killings and destructions.

Every action has a reaction, and the reaction another retaliatory action, which again triggers a reaction, creating a sort of an avalanche. The Hindu killings in Calcutta on the Direct Action Day immediately triggered Muslim killings in Calcutta and elsewhere, which in turn triggered horrific riots in Noakhali in East Bengal in October, unleashing another round of Hindu genocide, which led to the Bihar killings of the Muslims, which again had catastrophic impact on the ongoing Noakhali riots. The Great Calcutta Killings left 7000 to 10000 dead, both Hindus and Muslims. In the Noakhali riots more than 5000 Hindus were killed, villages after villages were burned, innumerable Hindu women were raped and many were forcefully converted to Islam. In Bihar 2000 to 3000 Muslims were killed. The Noakhali riots were so horrific that Gandhi had to camp there for months, to get things under control. [14]

By end of 1946, it was clear that the League wouldn’t allow the riots to stop till the demand for Pakistan was met.

When the partition finally happened in 1947, East Pakistan had a staggering 11.4 million Hindus, who by now, had realized that they wouldn’t be safe, for sure, in what had already become East Pakistan. Unlike Punjab, here it was not possible for such a huge population to flee East Bengal overnight. As they trickled into India slowly, over the years, carrying with them never heard of horrific stories of one sided Hindu genocide of massive proportions, Nehru, then the Prime Minister, came up with an ill-conceived idea, much to the protests of people like Shyama Prasad Mukherjee, the founder of the organization which eventually evolved into the present Bharatiya Janata Party. [12]

To prevent the Hindu exodus from East Bengal, Nehru entered into a pact with the government of East Pakistan to help create favorable conditions for the post 1950 Hindu refugees to go back to their original homes in East Bengal. It’s really surprising that such a plan was never implemented in the Punjab.

The only reason for such an action could be the same old fetish for a ‘secular’ garb, at any cost, something which we had come across a decade ago when the Congress didn’t want to enter into a coalition with a Muslim party, lest it got tagged as a counter Hindu party. Accepting the disproportionately large number of Hindus from East Bengal would destabilize the Hindu-Muslim parity in the share of violence inflicted by each side. It would expose the uncomfortable truth that in Bengal the violence was inflicted predominantly by the Muslims against the Hindus. The very fact that only 700,000 Muslims migrated to East Bengal from the west, against the eight million Hindus who would eventually move into India over the years, is proof enough that the violence in Bengal was one sided, against the Hindus. In Punjab though, it maintained the much sought after parity, which would make both the Muslims and the non-Muslims equally devil. Any disparity in this regard would be uncomfortable for the idea of secularism. The Bengal side of the partition didn’t fit into a particular kind of narrative of Hindu-Muslim equality, which is rather more impractical and utopian than idealistic. The disparity also had another danger – the retaliation. The moment the rest of India would come to know of the magnitude of the atrocities against the Hindus in East Bengal, there ought to be retaliation and chain reactions of communal violence. It might not be an over statement, if it’s said that India owes its secularism to the Hindus of East Bengal, who never got to tell their stories to the world.

Proponents of secularism (or should we call them Hindu-Muslim parity seekers?) often try to underplay the one sided nature of the violence against the Hindus in East Bengal by highlighting sporadic cases of Muslim killings and violence against them in West Bengal during the partition. There’s no denying the fact that there was indeed some amount of violence against the Muslims too, but that didn’t create an atmosphere of mass exodus of the Muslims from West Bengal to East Pakistan. The present demographics in West Bengal corroborate the same. The proportion of the Muslims in West Bengal during partition was 25% [1] and now it’s actually more, 27%, whereas the proportion of Hindus in East Bengal (now Bangladesh) has come down from 30% [1] during partition to 8% now.

Figure 4: Comparison of Demographics in the Punjab and Bengal - 1947 & Now

Nehru, very smartly, tackled everything with a single master stroke, by giving an impression to the rest of India and the world that things in East Bengal were so favorable to the Hindu minorities that they were returning to their “home”. Much to Nehru’s relief came the Bengali intelligentsia, the writers and the poets, most of whom had left leanings, and felt the same about the Hindu-Muslim parity. For them too, the acknowledgement of the plight of the Hindus in East Pakistan would conflict with their utopian idea of Hindu-Muslim equality. So, no one uttered a single word, and a big part of the narrative of the Bengal partition was consciously brushed under the carpet. Not surprisingly, India didn’t sign the 1951 UN Convention on Refugees and subsequently, the Bengal partition escaped the attention of the world.

Under Pakistan, the condition of the Hindus in East Bengal deteriorated drastically. They were always looked at with suspicion, as though they were all Indian agents. When the people of East Bengal, irrespective of religion, protested against the imposition of Urdu on them by the federal government, the Hindus were again at the receiving end of the Pakistan Army’s wrath, as they thought the Hindus, with their India leanings, were instigating, influencing and corrupting the Muslims of East Bengal. Even a theft of a holy relic from the Hazratbal shrine in Srinagar, in Kashmir, lead to killings of Hindus in 1963. Hindu genocide, on any pretext, continued for years, and it culminated in 1971, during the Bangladesh war of liberation, when around 2.5 million Hindus were killed by the Pakistan Army. [15] Compare that with the five to six million Jews killed in Holocaust. [14]

Figure 5: Hindu Genocide by Pakistan Army in 1971 & other Genocides in the recent past

The Hindu genocide in East Pakistan and Bangladesh, since the Bengal Partition in 1947, might need a little more background for a better understanding. Dr. Hans Hock, a faculty of Linguistics & Sanskrit and an Emeritus Professor at UIUC, summarized it quite well in his talk Banglatā, Islam, and Language, at the panel on Borderland Narratives of the Bengal Partition. Dr. Hock said, “there is and has been a dual identity for many Bengali Muslims, especially in East Bengal, a tension between what may be called Banglatā and Islam.” [16] Banglatā, or the Bengali ethnic and linguistic identity of the Muslims of East Bengal or East Pakistan, often superseded their Islamic religious identity. For the Hindus though, there was never any confusion with regards to the identity – they were just Bengalis. Right after the creation of Pakistan, Banglatā posed a severe threat to the very idea of Pakistan, which very strictly centered around an exclusive Islamic identity. Any other identity was not at all acceptable.

Immediately after 1947, Hock said in his talk, the government of East Pakistan proceeded to remove Bangla from its currency and postal stamps. The minister of Education, Fazlur Rahman, started the procedure of making Urdu the single official state language. Students protested in December 1947 and March 1948. They were joined by numerous East Bengal intellectuals, both Muslim and Hindu. Jinnah condemned the Bengali language movement as an effort to divide Pakistan. He said, “The State Language of Pakistan is going to be Urdu and no other language. Anyone who tries to mislead you is really the enemy of Pakistan. Without one State Language, no Nation can remain tied up solidly together and function. Look at the history of other countries. Therefore, so far as the State Language is concerned, Pakistan’s language shall be Urdu.”

This subsequently led to the violent suppression of the Bhasha Andolan, the Bengali Language Movement, in East Pakistan by the Pakistan Army on 21st February 1952 – the day commemorated now as the Mother Language Day worldwide. Tensions continued, and then, in 1971, “Operation Searchlight” by the Pakistan Army against the Bengali intelligentsia and cultural institutions, as well as the Hindu minorities, lead to some 10 million fleeing to India, and some three million being killed, of which a massive 2.5 million were Hindus. Interestingly, the Urdu-speaking Biharis, who had moved to East Pakistan from the Indian state of Bihar after 1947, played a major supporting role in the genocide. Finally, with intervention from India, Bangladesh was declared independent in December 1971, at the end of a very decisive war between India and Pakistan, where the latter had to swallow and very inglorious defeat.

It was expected that Bangladesh, the country which was created on linguistic lines, would turn out to be secular. But, sadly enough, “atrocities [against the Hindus] recurred numerous times after 1971, driven by Islamist groups. At the same time, many Bangladeshi intellectuals protested against these events, including the well-known writer Taslima Nasrin [she wrote the controversial book Lajja, Shame], who had to go into exile in 1994 and, [ironically], met with opposition in India as well.”

Though the Banglatā, Hock referred to, does play a crucial role in the identity of the Muslims in Bangladesh, but there have been numerous instances when the frenzy Islamic identity overtook the ethnic and linguistic identity, ever since the Muslim League declared the “Direct Action” in 1946.

Unlike the population migration in the Punjab, which happened in one shot, the Hindus left in East Bengal, and then Bangladesh, have been trickling into India continuously, over the years, till this day, being constantly under the threat of violence and genocide. They were always unwanted and never accepted properly, or rather legally, by Indian government.

The very tenet of the partition of India was to carve out a safe “home” for the Muslims. This simply implies, by contrast, that the rest of India should provide safety to the non-Muslims of the sub-continent, because otherwise there wouldn’t be any “home” for them. So, providing sanctuary to the Hindus of East Bengal and Bangladesh was the moral obligation for India. Here too, the same obsession for a particular form of secularism played a big role. It was as though, accepting the Hindus facing persecution in Bangladesh would be tantamount to being partisan to the Hindus, and hence being communal.

The complete denial of the plight of the Hindus in Bangladesh, and more shockingly, the banning of Taslima Tasrin’s books about the same in secular India, seems to be in continuation of the leftist zeal of finding a Hindu-Muslim equality, something which has been in vogue for a long time, as we’ve seen earlier. That’s the reason why one of the biggest genocides in modern human history – that of the Hindus in East Pakistan and Bangladesh – has been thoughtfully and very consciously sunk into oblivion. It is as though, till there’s an instance of an equally massive Muslim genocide by the Hindus, talking about the Hindu genocide in East Pakistan and Bangladesh would disrupt the much desired Hindu Muslim parity. Secularism is “the principle of separation of the state from religious institutions”. So, going by that definition, the very act of the state (whether India or West Bengal) of controlling (read erasing) the narrative (read plight) of one particular religious community (read Hindus), is nothing but the state itself acting like an institution with vested religious interests. Hence, this overzealous attempt of trying to be secular actually makes the state as communal as it could be. Then, there’s no difference between Pakistan, which has very consciously tried to eradicate its non-Islamic past, and West Bengal or India, which, has also very consciously tried to eradicate an un-Hindu past (of the Hindu genocide in East Pakistan and Bangladesh). A similar attempt is never taken, in the name of secularity, when sporadic contrary incident happens. Even a military action against Muslim terrorists in Kashmir is painted in communal colors, as the subjugation of the minority Muslims under a Hindu majority state.

Something even more curious is the case of creating the myth of Hindu Terror. The CPM General Secretary Sitaram Yechury has recently said that Hindu mythologies like Ramayana and Mahabharata prove that "even Hindus can be violent". [17] In January 2013, the then Congress Home Minister of India, Sushil Shinde, used the term "Hindu Terror" in an official statement. In August 2010 too, the then Congress Home Minister of India, Chidambaram, used the term "Saffron Terrorism" in an official statement. [18] Secularism has really come down to creating "parities". If there's terrorism perpetrated by Islamist radicals like the ISIS, there must be a “Hindu Terror” too, just for the sake of parity.

It’s important to delve into the real narrative of the Bengal side of partition, not with an agenda to create communal divide, but to know the truth. Suppressing facts to serve a particular agenda, to align everything to one particular narrative, is not secularism – it’s as totalitarian and majoritarian as being extremely communal.

Selected References

[14] Wikipedia

Others

1.

https://thewire.in/history/partition-70-less-explored-narratives/amp/

2.

http://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Partition_of_Bengal,_1905

4.

http://theconversation.com/how-the-partition-of-india-happened-and-why-its-effects-are-still-felt-today-81766

5.

https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2017/08/haunted-unification-bangladeshi-view-partition-170813093154943.html

6.

https://web.stanford.edu/group/SITE/archive/SITE_2010/segment_5/segment_5_papers/jha.pdf

7.

http://www.asiaportal.info/ethnic-cleansing-and-genocidal-massacres-65-years-ago-by-ishtiaq-ahmed/

8.

https://www.unhcr.org/3ebf9bab0.pdf

9.

https://www.un.org/en/holocaustremembrance/docs/FAQ%20Holocaust%20EN%20Yad%20Vashem.pdf

10.

https://www.unhcr.org/figures-at-a-glance.html

12.

https://www.aljazeera.com/amp/indepth/features/2017/08/remembering-partition-slaughter-house-170810050649347.html

13.

https://jaipurliteraturefestival.org/partition-literature-writing-about-the-darker-side-of-independence/

14.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artistic_depictions_of_the_partition_of_India

15.

https://amp.scroll.in/article/847113/how-have-indian-novelists-depicted-independence-and-the-partition-heres-a-sampler-from-their-works