Event Date: Thursday, April 25, 2019

Time: 4:00 pm–5:00 pm

Location: Knight Auditorium, Spurlock Museum, 600 S. Gregory St., Urbana, IL

Co-sponsored by the India Studies Fund at the Center for South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign (UIUC)

Time: 4:00 pm–5:00 pm

Location: Knight Auditorium, Spurlock Museum, 600 S. Gregory St., Urbana, IL

Co-sponsored by the India Studies Fund at the Center for South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign (UIUC)

We have already heard about the background of the Partition of Bengal [from Professor Hans Hock’s lecture]. I would like to give a little more perspective because, I believe, the Partition of Bengal was not [done] in isolation – it was [a] part of the Indian partition.

My family is a victim of the partition of the eastern side. My father was only seven years old and my uncle was 14 years old. And… one fine morning, not in 47 but in 1948 – my father’s family didn’t move immediately, like most Hindu families. So, one fine morning, my grandmother – she just woke up, and she told my uncle, who was 14 years old, to take my father and my younger aunt, who was just five years old. What happened was something like this: A14-year-old boy – he becomes the guardian of a seven-year-old boy and a five-year-old girl. And they took almost 35 days to come from Barishal [to Calcutta]. Barishal is one of the divisions in Bangladesh which adjoins the Sundarbans and which is one of the southern [most] districts of Bangladesh.

I never went to Bangladesh like most of the second-generation Bengalis whose parents have moved [to India]. I never went to Bangladesh and I never saw all the horrors and all the violence myself. But what happened is this.

When I was growing up, I had one of my very old aunts who used to stay with us – she was a widow – and she used to babysit me when I was very young. My father and mother both were working. And a 70 plus year old lady, who had moved out of Bangladesh almost 35 years back – it was in the seventies – and [yet] her entire world was around Bangladesh. She had been staying in India for the last more-than-thirty years. She never got a chance to go back to her homeland but all she could talk about was all Bangladesh, which was East Bengal. And I grew up hearing only stories of not only partition but also various other things, like the village fairs, about some very insignificant things which nobody might even remember. But that old aunt – she used to again and again tell all the stories. And [as] for a five-six-year-old child, who should be treated with more of fairy tales… and all these things, and… I grew up with the fairy tales of Bangladesh.

And then she died in 82-83… and life moved on. And [then], somewhere in the 2007 or 2008, when I thought that I would take up writing, I figured out that the stories that I have heard about the partition, and also about Bangladesh – those are actually a treasure trove to me. And another very interesting thing which I figured out [was] that there was absolutely nothing available about the Bengal side of the partition. When we talk about the Indian partition it’s always the Punjab side. Whether it’s in the movies, whether it’s in the literature or whether it’s in the… the common psyche of Indians. None of my friends and colleagues even knew that Bengal was also partitioned. Because, with movies, Hindi movies, and also the Punjabi writings, which were already getting translated – like, Amrita Pritam Singh is one the fantastic Punjabi writers, and we have Bhisham Sahni, and then we have Krishna Baldev Vaid – there was [a] huge amount of literature available in Punjabi and also in English – Khushwant Singh had written a fantastic book called Train to Pakistan. So, what made me curious is, why is it so that two states were partitioned at the same time but somehow the narrative of Bengal has been totally forgotten? Nobody knows about it. I searched in goggle. Absolutely… absolutely no material.

And at this juncture I would like to refer to one of the very distinguished guests, who’s here in the audience – Mr. Rajmohan Gandhi. I read one of his books, Mohandas. And… while I was thinking [of] writing about Bengal partition, [I found] his book has one chapter about the Noakhali riots and I believe that was one of the very few materials which I got about what exactly happened in Bangladesh. So that’s where I wanted to figure out what was different in Bengal that it never got the attention.

And… [this is] just to put some perspective to the magnanimity and to the enormity of the issue. This, you see, is the undivided Bengal, which comprises both West Bengal and the present Bangladesh. The current Punjab in Pakistan is little different, but so is in India. The Indian Punjab has been broken into three states, Punjab Haryana and Himachal Pradesh. This is how India was partitioned.

And if you see the numbers – the idea of partition was to create a safe home for the Muslims, which [is what] the Muslim League used to say – the partition of Punjab was, I would say, sort of realistically done, where each side has almost four million of minorities. The Indian Punjab had around four million Muslims and the Pakistan side [of] Punjab had around four million non-Muslims, which included Sikhs and Hindus. So, the population exchange was very similar. Four million from here to there and four million from there to here.

But in the Bengal side, almost eight million, sort of, non-Muslims were there in Bangladesh, and of course West Bengal had a huge population of non-Hindus, Muslims.

But, very interestingly, only seven hundred thousand Muslims from West Bengal moved to East Bengal. Very recently, I read an article written by a Bangladeshi journalist in [the] New York Times – it was published during the seventy years of Indian independence – and there also, he mentions the same figures, that only 700K Muslims travelled from West Bengal to East Bengal, and that also, not due to violence. They moved because of better opportunities, because they felt that a Muslim majority country might have more opportunities for them.

And, if you see, this eight million, who moved from East Bengal to West Bengal – they didn’t move in one shot. Because eight million people can’t move in one shot. It’s like twice the [size of] population transfer that happened in the Punjab. They trickled into West Bengal over a very long time, starting from 1947 till 1971, when Bangladesh was liberated. And my own family moved towards the end of 1948.

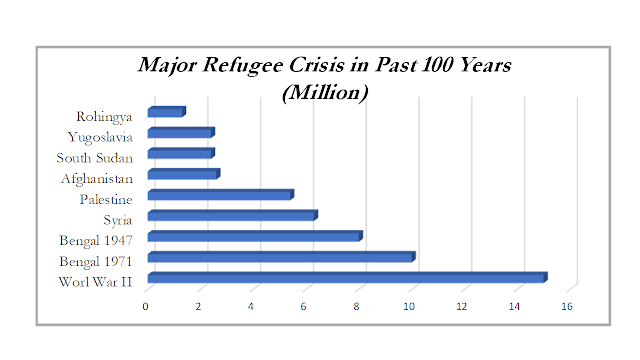

So even if you see, by sheer number, it’s double the size of Punjab partition. And also, it’s a very one-sided affair. It’s not population exchange. And here, then again, what sort of makes me even more curious [is], if you compare the refugee crisis, that happened over the last 100 years: World War Two created around 11 to 20 million [refugees] so I took 15 million as the median number; Bangladesh [Liberation] 1971 created around 10 million, and the 47 [Bengal] partition created around 8 million refugees. So that’s among the highest in the world, and that makes the Bengalis of East Bengal, who moved to West Bengal, the second most… second largest displaced community in the world, if you go by these numbers.

But interestingly, in West Bengal – and I’m very proud of it, that I’m a native of West Bengal – the population percentage of Muslims didn’t reduce in [independent] India. Somehow, India managed to maintain its secular fabric. West Bengal had around 25% Muslims in [19]47 and now its 27%. So… I would like to request the Western Academicia to do some research, [as to] why is it so that such a big event, and such a big refugee problem, such a big displacement in the world, which the Bengal partition created – why was that totally forgotten?

I don’t have any clear answer for that. But I believe I would request some academic research to figure [that] out. At least for [the next generations of the] refugees, like us – okay, I’m not a refugee [par say], but I think the only solace for a refugee is to see other people sympathizing them, to see [a] lot of literature written about them. The Jews – one of the best consolations for them is the huge amount of literature, films, movies created on them. So, they realized, “Fine, I’m not alone.” There are millions of sympathizers for them. But the Bengalis of the Bengal partition – we don’t even have that solace. Nobody writes about us. Nobody talks about us.

Thank you.

No comments:

Post a Comment