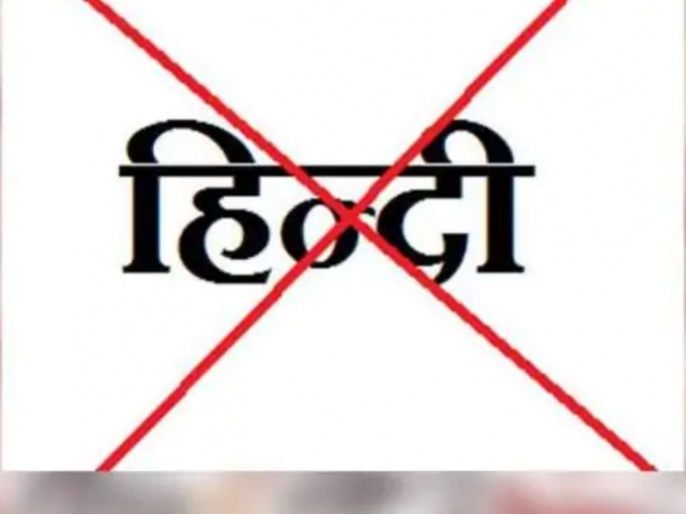

From time to time the diatribe against the imposition of Hindi on non-Hindi speaking people of India has become a sort of fashion, or rather a political weapon, to be flashed in public in order to flaunt nothing but a form of hollow chauvinism – it could be termed anything like provincial, regional, linguistic, ethnic, etc. – and mislead the innocent people with a fake sense of psychological safety against an imperial or federal onslaught. For reasons better known than often told, Hindi has been seen as a symbol of imposition and a threat to the pluralistic identities of India.

But strangely, the same threat is not felt for English, which, warns the prominent French linguist Claude Hagege, “may eventually kill most other languages". That itself says a lot about all these protests. These are just selfish acts of politics “concerned with the self-interest of a pugnacious nationalism”, to use Tagore’s apt words. I dragged Tagore into this because his views about “nationalism” are perhaps the most practical and relevant ones, even today. The “nationalism” he has referred to would be very clear from what he has to say about “nation”.

“We have no word for Nation in our language,” he clarifies. “When we borrow this word from other people, it never fits us… Not for us, is this mad orgy of midnight, with lighted torches…”

Orgy of midnight, with lighted torches? Did the poet have a premonition of all the candle-lit vigils at the India Gate?

We will come back to Tagore. For now, let’s talk about something more recent. The moment the draft of the National Education Policy 2019 was made public, “lighted torches” came out in the night, accusing of, the same thing – imposition of Hindi.

I actually went through the draft.

It says, “Because research now clearly shows that children pick up languages extremely quickly between the ages of 2 and 8, and moreover that multilingualism has great cognitive benefits to students, children will now be immersed in three languages early on, starting from the Foundational Stage onwards.”

It then goes on elaborating the Three Language Formula: “[It] will need to be implemented in its spirit throughout the country, promoting multilingual communicative abilities for a multilingual country. However, it must be better implemented in certain States, particularly Hindi Speaking States; for purposes of national integration, schools in Hindi speaking areas should also offer and teach Indian languages from other parts of India. This would help raise the status of all Indian languages…”

What’s offensive in this? I don’t see any.

Just in case people think that the draft came from some arbitrary people, it must be reminded that the chairman of the committee is none other than K. Kasturirangan, former Chairman of ISRO. Few members are Vasudha Kamat, former Vice-Chancellor of the SNDT Women's University, Bombay, Manjul Bhargava, R. Brandon Fradd Professor of Mathematics at the Princeton University, USA, Mazhar Asif Member, Professor at the Centre for Persian and Central Asian Studies, School of Language, Literature and Culture Studies at the Jawaharlal Nehru University, and others. I don’t think these people could be categorized into any genre of arbitrariness.

In case people have second thoughts about the benefits of multilingualism, let’s consider these.

Brainscape, committed to improving how the world studies, using the latest cognitive science research, has cited many benefits of being multilingual. Multilingual people, they say, tend to be more effective communicators. Multilingualism can even delay the onset of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease by an average of five years! Multilingual people better perform on tasks that require high-level thought, multitasking, and sustained attention. Perhaps this is why they are often seen as more intelligent than peers with similar innate intelligence, education, and background. They tend to solve complex problems in more creative ways than their monolingual peers, no matter what kind of problem is being solved. They are faster learners, more likely to make rational decisions, keen observers of the world around them, and more skilled at identifying and correctly analyzing the sub-context of a situation and interpreting the social environment.

An article in The Guardian says, multilingualism has been shown to have many social, psychological and lifestyle advantages.

To the question whether we should raise our children to be multilingual, The British Academy says, “My answer is an unconditional yes.”

In addition to facilitating cross-cultural communication, a paper says, multilingualism enables children as young as seven months to better adjust to environmental changes and seniors to experience less cognitive decline.

So I believe the question why three languages should be taught from early days is answered quite well. Let’s move on to the most important thing – the explosive topic of learning Hindi for non-Hindi speaking people.

Let’s rewind a bit. In 1918 Gandhi wrote a letter to Tagore asking if Hindi could be the “possible national language for inter-provincial intercourse in India”. Tagore’s answer was very interesting. “Of course Hindi is the only possible national language for interprovincial intercourse in India,” he asserted. “But… I think we cannot enforce it for a long time to come. In the first place, it is truly a foreign language for the Madras people, and in the second, most of [us] will find it extremely difficult to express [ourselves] adequately in this language for no fault of [our] own. So, Hindi will have to remain optional in our national proceedings until a new generation… fully alive to its importance, pave the way towards its general use by constant practice as a voluntary acceptance of a national obligation.”

Almost 20 years later, in 1937, Tagore wrote to Gandhi, “It is imperative … to organize an all-India movement to foster and spread the growth of a language which is potentially capable of being adopted as a common medium of communication between the different provinces… However, I hope that the language which is to claim allegiance as the lingua franca will prove and maintain its complete freedom from any communal bias…”

Intentionally I didn’t cite any or Gandhi’s words in favor of a lingua franca for India, because I felt, Tagore’s views are more universal in many aspects, and hence shouldn’t be colored either with left or right. Interestingly, Gandhi, who went a long way fighting for Hindi to be made as National Language (which hasn’t been ever implemented), and Tagore, both were non-Hindi speakers. But still they felt the need of a lingua franca, which has more relevance to trade and commerce than anything else. If the provinces were to stay in isolation, then there wouldn’t be the need for any lingua franca. But then, no province can grow in isolation. Unless there’s exchange of money and mind (thoughts), no race, province, nation can ever grow. And the first step for such an exchange is a common language, a lingua franca.

Neither Gandhi nor Tagore could be accused of anti-colonialism in not choosing English as the lingua franca. Whoever thinks that as an option is surely not a practical person. It’s ludicrous to think that a mason from Bengal and working at a construction site in Gujarat would bargain in English with the local fisherman, or, a Central Government employee from Madras, transferred to Assam, would teach the local cook, in English, how to make good sambar. It’s a no brainer that, even now, more than hundred years after Tagore had written that letter to Gandhi in 1918, Hindi is still the most likely solution to Tagore’s lingua franca for cross communication between provinces.

Many centuries ago, even the Mughals had felt the need of a lingua franca, for better administration and trade across the vast country of many races and languages. They too chose the prevalent Hindustani language of the day as the lingua franca. Of course they introduced a lot of Persian and Arabic words of administrative and judicial use. Thus, the Sauraseni Prakrit language of the medieval India, the immediate ancestor of Hindi during the first millennium, got a little different flavor in the second millennium, which later took the name Urdu, perhaps coming from the word vardi, meaning uniform, implicating that the language was nothing but a lingua franca for the people in uniform – either in the army or government jobs. Like Gandhi and Tagore, wisdom prevailed among the Mughals – they didn’t try to make Persian, their preferred language, the lingua franca. Persian, like English, stayed the official language for education, art and literature, whereas the lingua franca was the native Hindustani-Urdu.

More than two millennia ago, Ashoka too had a lingua franca – a form of the Magadhi Prakrit language (forefather of Bengali) spoken in Magadha, comprising present day Bihar and Bengal, Ashoka’s native. It might be relevant to note that in all of Kalidas’ Sanskrit dramas, the dialogues of the common people – the artisans, peasants, fishermen, even thieves – were always in Magadhi Prakrit, wherever they would be from. The only plausible reason for this could be that, Magadhi Prakrit was indeed the lingua franca of the common people across the country.

Ashoka’s rock edicts, few of which have survived till date across the Indian subcontinent, from Kandahar in Afghanistan to Bangladesh, from Delhi to Karnataka, had local variants of the Magadhi Prakrit, depending of the location, very much like the present day lingua franca, Hindi, which is spoken in different variants in different parts of India. The caricature and type cast of the Hindi spoken by the Bengalis and the South Indians, as immortalized in Bollywood by Asit Sen/Keshto Mukherjee and Mehmood respectively, says all about lingua franca – it’s more of a sort of an assortment of a number of mutually intelligible creoles rather than any uniform grammatically correct language. You like it or not, Hindi has already acquired that stature and no other language can replace that, how much ever “mad orgy of midnight, with lighted torches” you do!

Going further back, even during the times of the Indus Valley Civilization, in the second and third millennia BC, the entire Central Asia, the melting pot of civilizations, races, cultures and languages, extending into parts of northwestern India, is believed to have had a lingua franca – the Burushaski language, vestiges of which now exist only in a few villages in Kashmir. Quite interestingly, the word Sindhu, the eponymous river which lent the names and identities to India, Hindu, Hindi, Hindustan, and even Indonesia (literally meaning Indian Islands), and the far off Indians of the Americas and the West Indies, is of Burushaski origin – it has survived as a linguistic fossil of the once grand language and the lingua franca of the most important locus in the annals of human civilization.

Lingua franca is the foundation for growth and prosperity, without which, the people survive in isolation, without any interaction and exchange of mind and money. Bangalore reaped the benefit of exchange, as it was never averse to the lingua franca, Hindi, and hence attracted labor and talent pool from all across India, thus boosting the growth of the city. From a sleepy pensioner’s paradise even thirty years back, it’s now the forth richest city in India (with respect to overall contribution to GDP, after Bombay, Delhi and Calcutta), much ahead of Madras, which is still averse to Hindi. Not many people would feel comfortable relocating to Madras. But no one would have a second thought about Bangalore. Almost the entire construction industry in Bangalore is supported by laborers from Bihar, Bengal and Orissa, as is the new age IT, ITES and BT industries by people from all across India.

Despite all the hullabaloo about “Bombay for Marathas”, Bombay is still the most cosmopolitan city in India, attracting people from all walks of life – Bollywood is the biggest example. Bombay’s like a miniature India, and not surprisingly, the lingua franca is Hindi. No wonder it’s the richest city in India. Calcutta too, till very recently when the CM started talking about the Hindi speaking outsiders, was never averse to Hindi and outsiders from any part of India. That corroborates its position as the third richest city in India.

It’s not for nothing that the Tamil speaking Shiv Nadar, co-founder and present Chairman of the USD 8.5 billion HCL, famously said that Hindi shaped his career. He even asked students in Tamil Nadu to learn Hindi. Knowing Hindi immediately breaks many social barriers. In one moment, everyone becomes a member of a single large fraternity, irrespective of the backgrounds, castes, creeds. I realized this the best the moment I landed in Kharagpur, at the IIT. The initial discomfort in communicating in Hindi was overcome soon and I slowly started speaking a heavily accented Bong version of Hindi – not much different from how Bollywood depicts. Everyone at the IIT knew English, but it was only in Hindi that we could share the camaraderie and bonhomie which remained with us forever. The same level of jokes and jibes and fun and frolic is unthinkable in English, not because it’s incapable of the same level of humor, but because it perhaps lacks the mitti ki khushboo, the smell of the Indian soil which only a highly agile and extremely fluid variant of Hindi (or Hinglish, whatever you may call) has.

It’s quite clear that anyone who would be averse to learning the lingua franca would do more harm to the community or fraternity than any good. Relevant are Tagore’s words, again. “Swaraj is not our objective,” he says, in criticism to the overt “nationalism” during the pre-independence era. “Our fight is a spiritual fight, it is for Man. We are to emancipate Man from the meshes that he himself has woven round him — these organizations of National Egoism.” Language chauvinism is just another organization of egoism, nothing else, and the protectionism of the language in the name of nationalism is nothing but the “meshes … woven around”. Tagore adds, “The butterfly will have to be persuaded that the freedom of the sky is of higher value than the shelter of the cocoon.” Any sort of protectionism is nothing but sad attempts at keeping people in cocoons.

The very thought that a language would be threatened by Hindi is nothing but demeaning that language, trying to protect the language in a cocoon.

That’s bondage.

That’s like breaking the world “into fragments by narrow domestic walls”.

No comments:

Post a Comment